JELLYFISH

May 2022 – Portuguese Man-of-war (Physalia physalis)

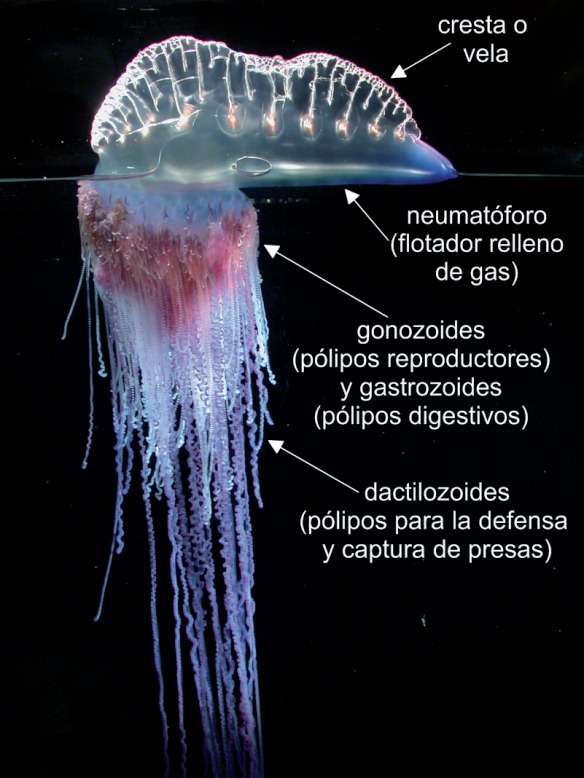

What do we know about the Portuguese Man-of-war (Physalia physalis)? To look at, is it a jellyfish? The answer is that the Portuguese Man-of-war is a colony made up of hydrozoan siphonophore organisms of the Physaliidae family. The individuals that make up the colony are specialists and each contributes to keeping it alive; that is, each group of hydroids has one specialised function, carrying out just one certain job: the pneumatophore (the part that floats or sails), the gastrozoids (the digestion), dactylozoids (detection and capture of prey, and defence) and the gonozoids (which deal with reproduction).

It is made up of a gelatinous sail of between 15 and 30 cm that allows it to cross the oceans driven by the winds, tides and marine currents. Numerous tentacles hang down from the central body and serve to catch its prey. Extended, these can measure up to 50 m, although they are more usually only about 10 m. These tentacles have stinging capsules called cnidocytes that can paralyse a large fish and seriously affect humans. These capsules, when activated by a stimulus, release a single-use hollow coiled filament called a nematocyst. These nematocysts can be of diverse morphology: simple suckers, long extensions of the tentacles that wrap around the prey, and spikes or spines that can inject a protein toxin that paralyzes it. The tentacles then wrap themselves around the prey and help to get it into the mouth located in the gastrovascular cavity, where the digestion starts. It usually captures small aquatic organisms such as fish and plankton.

Despite its powerful poison, the Portuguese Man-of-war has several predators, among them the Glaucus atlanticus slug, the Purple snail (Janthina janthina) and the Sunfish (Mola mola). When it detects these organisms, the Man-of-war can deflate its peculiar floating apparatus and sink right to the bottom of the sea, giving the impression of having died.

Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) turtles are also predators of these organisms, because their hide is too thick for the poison from the stings to affect them.

The Manta octopus is immune to its poison and is another predator of the Portuguese Man-of-war. A curious fact is that there is a very special relationship between a small fish, the Nomeus gronovii, and the Portuguese Man-of-war. This fish is partially immune to the poison of the stinging cells and can live among the smallest tentacles under the air bladder. The Portuguese Man-of-war is often found living with a variety of other marine fish, including Clownfish and Horse mackerel. Clownfish can swim between the tentacles with immunity, possibly due to their mucus, which does not activate nematocysts. All these organisms protect themselves from their predators by hiding in the tentacles of the Man-of-War and it in turn goes along with this because they attract other fish which make up the Man-of-war’s diet.

The Portuguese Man-of-war is found normally in the Atlantic Ocean, in tropical and subtropical latitudes, and is only found sporadically in the Mediterranean, so why do we have so many sightings lately? The answer is meteorological; due to the physiognomy of this animal and its absence of motor organs which would allow it to move independently, go wherever it wants to, its displacement depends on the wind. It goes wherever the wind takes it. The wind influence is much greater than that of the ocean currents, since on the surface of the water the Portuguese Man-of-War offers much more resistance to the wind because of its sail than does the submerged part.

The west winds heralded its arrival this winter. Given the persistence of the westerlies we have had from February to the end of April, numerous schools of Portuguese Men-of-war were swept from the maritime region between the Canary Islands and the Gulf of Cádiz to the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar. As many people will remember there were continuous westerly storms during this period.

The population of Portuguese Men-of-War is very sensitive to sea temperatures, radically decreasing its population when the temperature is in excess of 25ºC; In addition, given that it is outside its habitat, the lack of food reduces its already scarce possibilities of colonising the coldest areas of the Mare Nostrum, such as the Alborán Sea and the northern parts of the Western Mediterranean. According to data from the website of the Centre for Environmental Studies of the Mediterranean (CEAM), a large part of the Mediterranean coast is already close to or exceeds the 25ºC barrier.

This year the climate is also atypical, having a cooler spring and the storms coming later than usual. This has kept the Portuguese Men-of-War in the Mediterranean for longer than normal. They began to arrive in January and are still coming but in much lower numbers.

As it affects humans, the poison of the Portuguese Man-of-War has neurotoxic, cytotoxic and cardiotoxic consequences, producing very intense pain, and, on very rare occasions, even cases of death have been recorded (although they are less frequent than those caused by the sea wasp – Chironex fleckeri).

The most common reaction is to feel a burning and itching in the area where the poison has been inoculated. If the sting is stronger, it can cause pain, vomiting and fever. In the event of a sting from this animal, it is best to remove the remains of tentacles that may be stuck on the skin. Avoid directly touching the area so that the poison does not also get on the helper’s hands. Gloves, tweezers, a credit card or something similar can help to scratch them off.

Do not splash vinegar or ammonia on the affected area. Use salt water (not fresh water as this will increase the pain) on the surface of the affected skin. Then apply ice every 15 minutes to dull the pain. Shield the affected area from direct sunlight and stop the person scratching. Finally, if the symptoms of pain and itching persist, you should go to a medical centre where a professional health worker will prescribe corticosteroid creams or some type of oral antihistamine.

One good thing about the Portuguese Man-of-War is that it is quite easy to spot because of the sail. This is always visible, even from quite a distance. The monitors in charge of coastal management remove them as soon as they are seen and if there is danger, bathing is prohibited. How long they remain in our waters depends, firstly, on the wind direction and then on the temperature of the water.

JUNE 2020

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SNOW AND THE JELLYFISH ON OUR BEACHES

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW . . .

Researchers from the University of Malaga, have carried out a research project that reveals what may be a new way of predicting whether or not there will be plagues of jellyfish (especially of the Pelagia noctiluca species) on the beaches in the summer.

This study ties together two climatic events affecting the sea surface temperature in summer. The North Atlantic Oscillation and the Arctic Oscillation are air flows caused by pressure differences that, when combined, lead to a greater or lesser probability of precipitation in the form of snow in our country. A higher record of snowfall and snow accumulation in Sierra Nevada, translates into an increase in fresh water that reaches the sea after the thaw.

Because salt and fresh water have different densities, fresh water floats on the surface, preventing colder salty water from rising to cool the sea. This brings with it an increase in the proliferation of jellyfish, since the high temperatures help a rapid development of the gonads and therefore greater reproduction.

But the fact that they reach our coasts is determined by the so-called Anticyclonic Gyres of the Alboran Sea. Jellyfish often choose areas with few currents for reproduction, such as the centres of these gyres, so that there is usually a higher concentration of jellyfish in them. This “safe area” for jellyfish can be altered by winds or by the strong current that comes in from the Strait of Gibraltar, displacing the masses of jellyfish to the north, towards our beaches.

Therefore, to sum up: in a year of heavy snow, there is a higher probability of jellyfish. This summer, since there have been no major snowfalls, the investigators Raimundo Real and Professor Carmen Sala of the UMA – Ciencias del Litoral de la Costa del Sol predicts a low-to medium proliferation of jellyfish.

We encourage you to enjoy the fantastic beaches of Andalusia, knowing that few jellyfish will sting you this year.

SUMMER 2019 –

SUMMERTIME – JELLYFISH TIME

The species of jellyfish known as the Mediterranean or fried egg jellyfish (Cotylorhiza tuberculata) has increased in number on the Andalusian coast because the sea is warming up. The temperature of its habitat has altered its growth and reproduction and therefore there are more of them.

Here is a little tip for a jellyfish sting: Find the nearest First Aid Post and / or go to the A&E Department of the health services who can provide specialised treatment. In the meantime, to avoid further pain, you can administer first aid by removing the animal’s tentacles with hot water or dry sand, always protecting yourself with gloves or even a plastic bag.

To ease the pain, apply compresses soaked in cold water, lemon juice, vinegar or diluted ammonia to the affected area. DO NOT scratch or rub the area. The momentary relief will disappear and the pain will only increase.

Have a GREAT SUMMER

SUMMER 2012

JELLYFISH PLAGUE

The two species have visited us this summer on the beaches of the Costa del Sol, dragged by the currents. Rising temperatures have led to the massive presence of these jellyfish that became a danger to bathers, causing a public alert.

Many tourists witnessed the phenomenon in astonishment and dismay. The increase of jellyfish along this coast may be the result of the absence of its main predator, the sea turtle.

15TH OF AUGUST 2010

JELLYFISH ALERT!

The Jellyfish Aggregations Study and detection Campaign at the andalusian beaches is focused by our Association. We therefore, ask for early information, when jellyfishes will be observed between Marbella and Málaga

NOTICES TO PRO DUNAS:

Email: asociacion@produnas.org

Teléfono de contacto: 609 600 706

Do you want to receive our Newsletter?

Do you want to become a member or be our friend of the dunes?

Asociación ProDunas Marbella

The Association works tirelessly for the defence and preservation of the unique ecosystems that survive in the natural sand dune environments in the Province of Málaga; promotes the protection of native flora and small wildlife; promotes recovery, rehabilitation and conservation of interesting biodiversity of sand dunes areas in the municipality of Marbella.