SMALL SUMMER TALK WITH THE RTV TELEVISION AND ESTEFANÍA

11th of July of 2022: Our sea floor

Vegetation that can be found on our coastal sea floor

We often visit and enjoy the outstanding beauty of our coasts and beaches, without ever stopping to discover the immense world full of life that its waters harbour.

The coast of Malaga is a very rich and diverse space in landscapes; with beaches, cliffs, estuaries, dune systems and seabeds with ecosystems as important as the coralline ones in the rocky substrates, or the seagrass meadows in the sandy ones.

The seabeds of the Province of Malaga offer great biodiversity. This is the result of its strategic bio-geographic location, where species from the European Atlantic, from the Mediterranean, from the subtropical area of Northwest Africa, and endemic ones from the area of influence of the Strait of Gibraltar converge.

Our short version is that you can see more than 100 different species of sea or water birds, more than 30 coastal plants, more than 15 different cetaceans, four species of sea turtle, three of seagrass, more than 200 species of fish, more than 500 marine invertebrates including molluscs, crustaceans, echinoderms, coelenterates, polychaetes, bryozoans or sea sponges, and more than 150 species of algae.

Perhaps one of the most characteristic organisms that live in our waters and that we may have seen on more than one occasion on the shore or on the rocks are algae.

Algae are organism usually unknown to many of us, and yet they have many important characteristics, such as being the first link in the marine food chain. They provide food for other organisms. They also play a fundamental role in scientific studies and in food or in industrial matters.

Algae are part of a very varied group of organisms that can be unicellular or multicellular; they can live in both fully aquatic and just humid environments. What they have in common is that they are all photosynthetic. Unlike what we know as plants, algae do not have truly differentiated tissues such as roots, stems, leaves, or vascular systems, and they do not produce flowers or seeds. Their evolutionary history is totally different.

They have chlorophyll and may have other accessory pigments. Their coloration, therefore, can vary depending on the presence of one or other of these pigments, dividing, according to this criterion, into three main groups: green (Chlorophyta), brown (Phaeophyta) and red algae (Rodophyta).

Like land plants, they are autotrophic organisms, that is, they are capable of producing organic matter from CO², water and mineral salts and, as a by-product, they produce oxygen. This data is interesting since these organisms are capable of taking excess carbon dioxide from the air, thus removing it from the environment and generating biomass from it. They are, therefore, considered to be carbon sinks. In addition, they need nitrogen and phosphorus. These they obtain from off flows or residues from, among other sources, city waste and urban pollution. This is very significant since, in eutrophicated waters, algae can be used to extract excess nitrogen and phosphorus, purifying them and, later, this biomass can be used to manufacture goods.

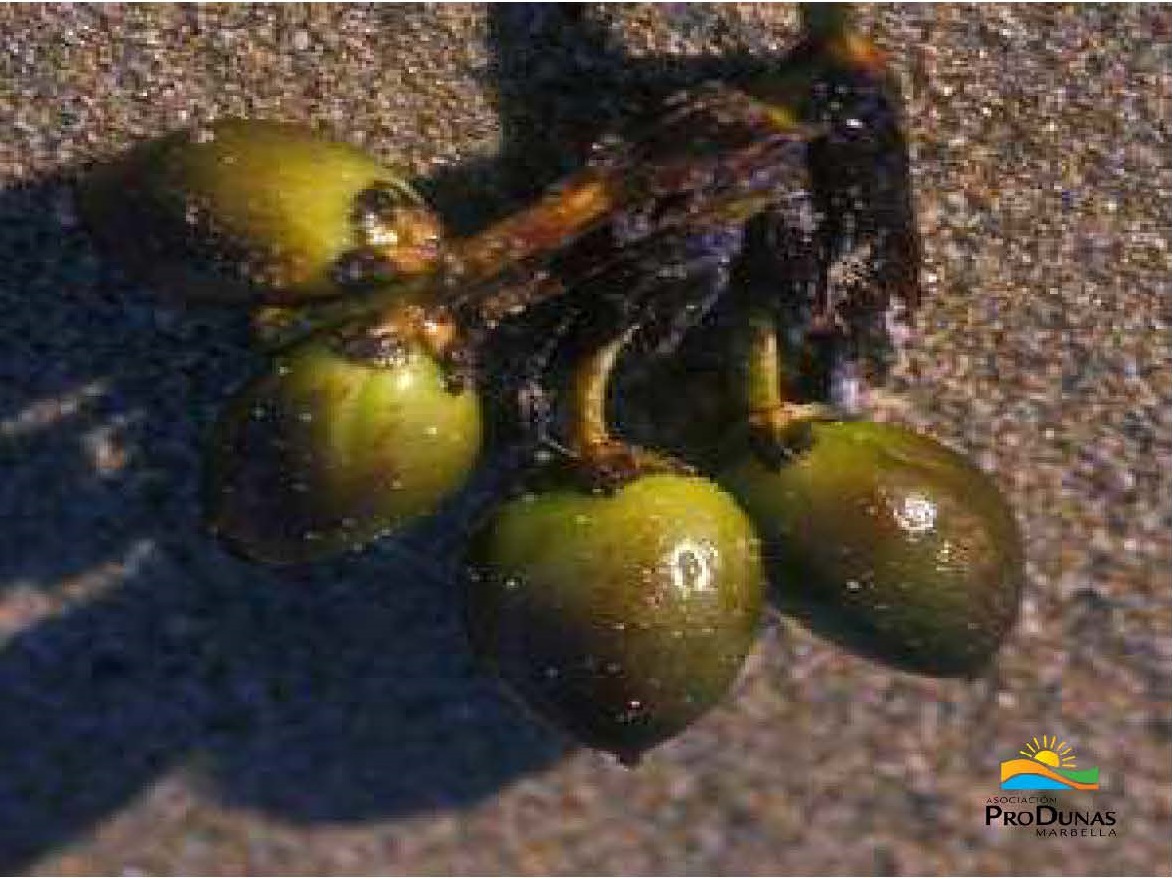

It is important not to confuse algae with marine plants or seagrasses, such as Posidonia oceanica or Cymodocea nodosa. Phanerogams are higher plants in evolutionary terms, so, unlike algae, they do have leaves, stems and roots, in addition to generating flowers and fruits. They present, therefore, a conductive system by which they absorb salts through the roots and distribute them through the sap throughout the entire plant.

Next, let us study the seabed of our waters to discover the most important and easiest plant species to identify. In this way, any day spent enjoying our coasts, either just strolling along or spending a day on the beach, we will be able to recognize and admire the beauty and biodiversity that our waters harbour.

Dictyota (Dictyota_dichotoma): brown algae. This is easy to recognize because it is flat with dichotomous branching, that is, it branches two by two. This species is endemic to our waters, that is, it is typical of our coasts and is not found in any other area of the world. We find it on rocky substrate, in the infra-littoral zone, where the light can get through to it and there is not much wave activity. These species form communities, making them ideal habitats for many species of invertebrates. They can also deal with a certain level of pollution.

Sea lettuce (Ulva sp.): green algae. This is very easy to identify because, as its name suggests, it looks a lot like a lettuce leaf. It is found on rocky substrates, although it is easily ripped off by the waves and can be seen washed up on the shore. It is resistant to pollution, and is always used in the eutrophication of water. For this reason, it can sometimes be an indicator of low water quality due to contamination, stagnation and other causes. It is used in the food industry.

Gelidium (Gelidium latifolium): red algae, shaped like a bush, with a rigid and cartilaginous consistency, highly branched. It is a species that lives on rocky substrates in the infra-littoral zone, located especially in higher areas where sunlight reaches it well. It is an important source of agar (gelatinous substance, widely used as a thickener and in medical laboratories as a culture medium for microorganisms).

Now we come to the world of seagrasses, where we find above all two very important and emblematic species in our depths:

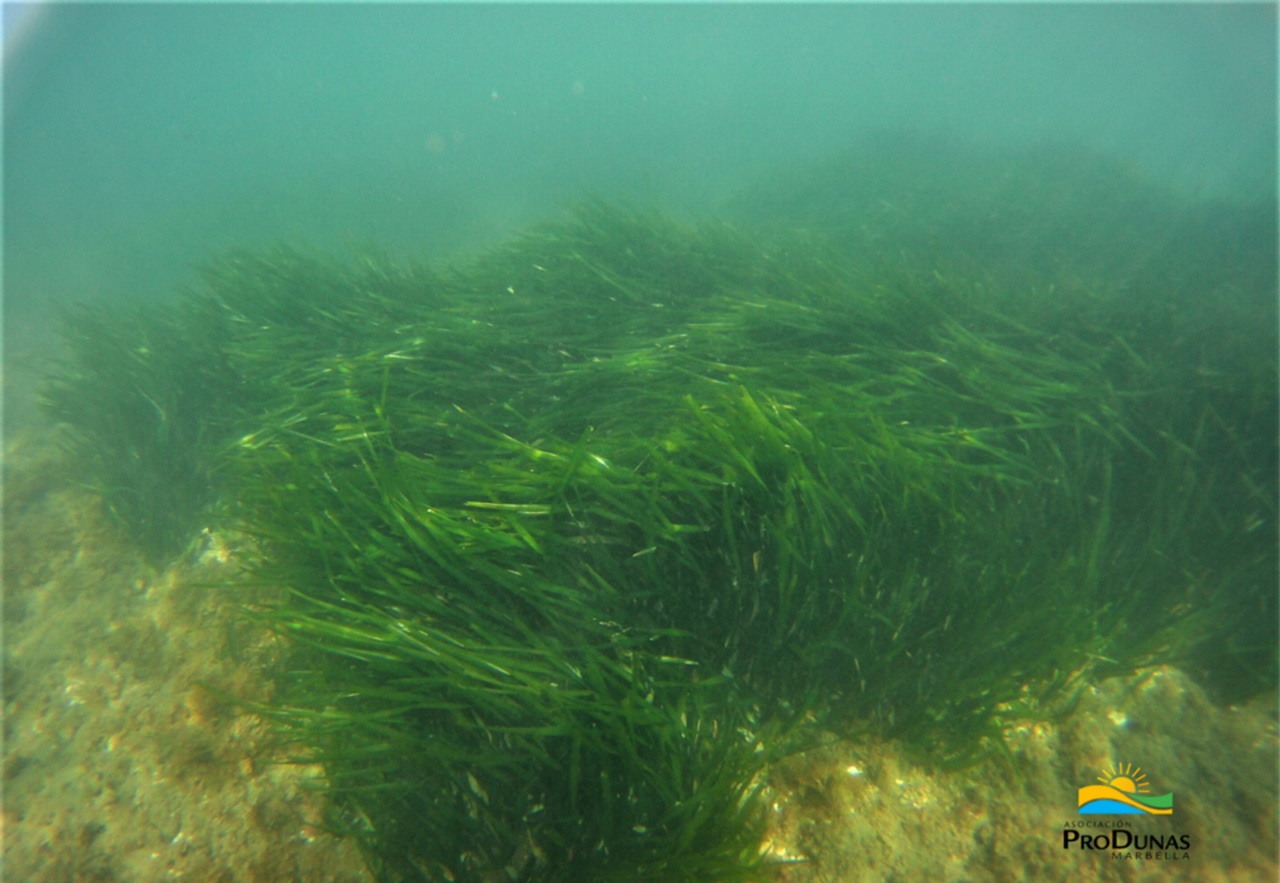

Cymodocea nodosa: This, after Posidonia oceanica, is the second most important marine plant in the Mediterranean due to its size and the extension of its formations. It is a herbaceous plant made up of stem, roots, leaves and flowers. It is also a colonising plant, typical of the Mediterranean and the nearby Atlantic with wide environmental tolerance. It develops in the infra-coastal zone, on sand or mud bottoms, with weak or moderate wave activity. Despite the fact that there are many scientific authors who continue to question its presence on the coast of Malaga, recent studies by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) testify to its presence, here and there in the Natural Park. Cliffs of Maro-Cerro Gordo (Maro), at Cabopino and Estepona, along with Posidonia oceanica and Zostera marina in Cabopino and in the Bay of Estepona, along with the last traces of Posidonia meadows. The Cymodocea nodosa meadows are of great ecological interest both because of the increase in animal diversity that their presence assures, and because they develop on soft bottoms, stabilising them and possibly serving as precursors to the establishment of another seagrass such as Posidonia oceanica, which does form dense meadows – true underwater forests. This species can be considered an indicator of good environmental quality, since it is sensitive to organic or industrial pollution.

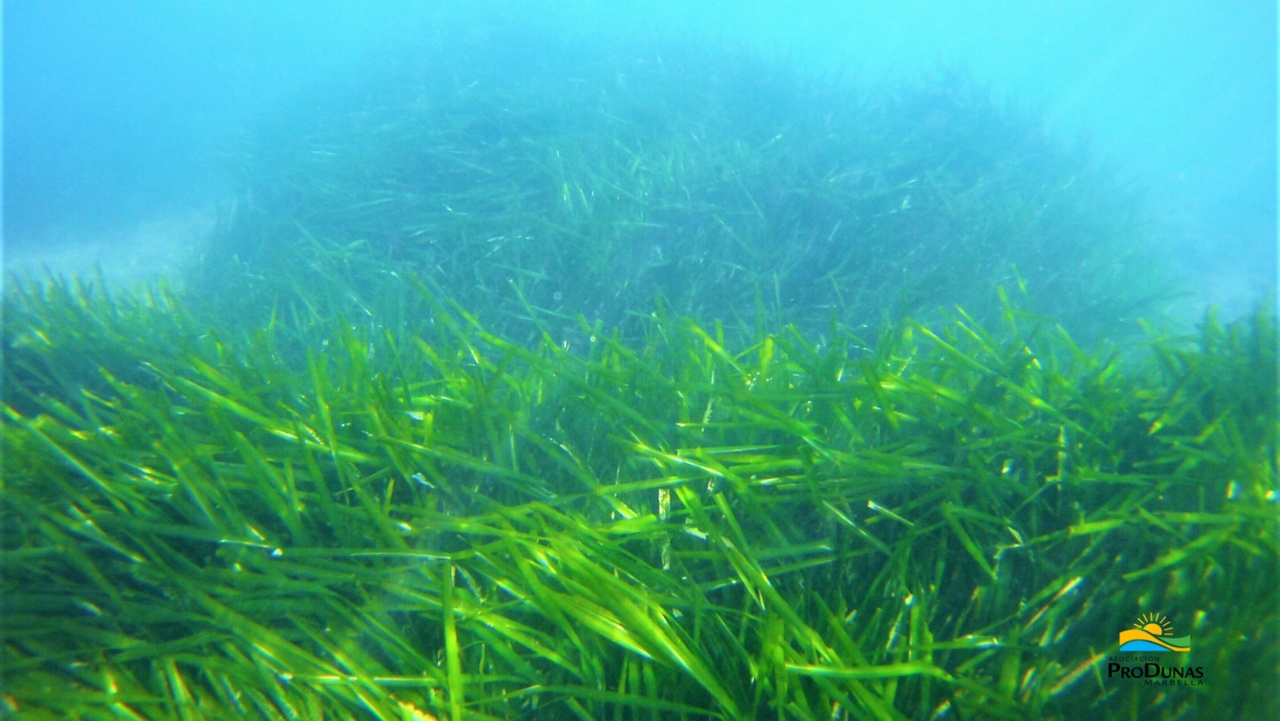

Posidonia oceanica: it is ´higher up the evolutionaly scale, so, unlike algae, it has leaves, stems and roots, in addition to the ability to generate flowers and fruit, with the difference that it lives submerged. The way to find it in the natural environment is to look for the meadows it develops. The leaves are flat and ribbon-shaped. The swathes of Posidonia oceanica form extensive underwater prairies as they grow, forming very stable and long-lived structures, but which at the same time are subject to very delicate balances. This is an endemic species of the Mediterranean that is not present in any other sea in the world. It can be found between the surface level and a depth of 30-40 m depending on the transparency of the waters, since it needs sufficient sunlight to carry out photosynthesis. Being an endemic species of the Mediterranean, one could expect to find similar stands along the entire coast of Malaga, but this is not the case. Given the conservation problems that this species has been exposed to over the years and the Atlantic influence it has to deal with as we move into the western coast, it is much easier to find it on the eastern coast, its maximum growth in the province being found in the Acantilados de Maro-Cerro Gordo (Maro) and in Calahonda – Cabopino (Marbella). Posidonia oceanica is very sensitive to pollution, which is why it is considered a good bio-indicator of water quality. The increase in pollution on the coast has caused a considerable reduction in its meadows, in spite of the construction of waste water treatment plants and quality control systems being put in place. However, it seems that this decrease is stabilizing. The slow growth of the prairies means that decades will be needed to be able to confirm this trend.

ProDunas Association of Marbella is at the beginning of a new and exciting project: The Monitoring and Study of the Seagrass Meadows on the Coast of Marbella (Málaga) – their Restoration and Conservation. This is aimed at leading to the improvement and protection of the beaches and dunes of Marbella and surrounding areas. We are proud to be part of this project which is being carried out in conjunction with the University of Malaga (UMA).

For months we have been getting ready to enter this silent, mysterious and magical world. We hope to discover what is in this underwater world on the Costa del Sol – unknown to many of us. We want to know if there are still meadows of these marine angiosperms on our coastline (Posidonia oceanica / Cymodocea nodosa and – less likely: – Zoster marina or noltii).

Most of the seagrass meadows (Posidonia oceanica, Cymodocea nodosa, Zoster noltii) that we find on our Andalusian coasts are located in areas that correspond to marine protected areas (AMPs). In Marbella we have small nuclei of populations of these species, which are not classified as ‘refugees’ and are therefore not under any protection framework.

We consider that the conservation and restoration of these nuclei are of vital importance since, in addition to being endemic species of the Mediterranean, catalogued as threatened species on the Mediterranean Red List and included in Annex II of the Habitats Directive, these areas belong to the westernmost populations of the Mediterranean. These ecosystems must be maintained in order to reduce the continuous loss of biodiversity that these waters are suffering.

This project will track the following main objectives:

- the conservation of biological diversity and marine ecosystems in our region, thus preserving species that are essential for the sustainability of these habitats in the Mediterranean;

- the promotion of research, development and use of new technologies and processes, in order to mitigate the effects of the climate change in progress;

The existence of and, therefore, the conservation of these populations of seagrasses on our coasts generate a series of positive factors that must be considered and conserved:

- They are a bio-indicator of good water quality. They contribute to keeping the waters more crystalline thanks to their ability to store sea sediments.

- They have great influence on different ecological processes such as wave attenuation, material retention and sediment fixation; helping to mitigate the effects of the very great erosion suffered by our coastline. They manage to reduce the force of the waves, protect the coastline and help preserve the beach-dune system, and contribute to the formation of sand.

- They are of great ecological importance, since they act as a sink for the organic carbon that is dissolved in the water. They mitigate the effects of large CO² emissions, helping to fight climate change. It is estimated that the amount of CO² that these underwater meadows can trap exceeds the action of terrestrial forests.

- The populations of seagrasses also constitute the natural habitat of other species of flora and fauna, providing them with shelter and protection, so their degradation would have a knock-on alteration effect in the natural ecosystem of many other species.

Causes of possible disappearance or reduction in the extension of seagrass meadows:

- Marbella is located at the very limit of the zone where the Posidonia oceanica in the Mediterranean (Alborán Sea) can exist. It could be that the small number of populations found naturally in this westernmost area are in equilibrium with the environmental conditions and that we are facing a natural limit of distribution.

- Cabopino harbour is close to the area on which we propose centring our project. This structure, in addition to slowing down the natural dynamics of the sediments in the dune ecosystem, acts as a barrier to seagrass seeds or propagules being dispersed from the meadows found just to the east of the Port of Cabopino, specifically in Calahonda (Mijas), where there are large populations catalogued as a ZEC zone (Special Conservation Area).

- Our geographical location plays a very important role in the development of this endemic Mediterranean seagrass. We are very close to the Strait of Gibraltar, an area where the waters from the Atlantic and the Mediterranean converge. On the one hand, the warm and salinized waters of the Mediterranean mix with the others with cold and less saline waters from the Atlantic, generating a descending slope of -125 mts and giving rise to masses of water that do not mix in the strait.

- This gradually diminishes as we get farther into the Mediterranean. In Marbella you can still appreciate the influence of the Atlantic in its waters and these environmental conditions may create a limiting factor that weakens the development of these meadows in our waters.

- Account must also be taken of the currents that cross these areas. Strong flows are generated that can affect the development of these seagrasses. Equally, we must remember the storms which usually hit our coasts especially in autumn and winter, can cause disturbances in the water environment that prevent a proper growth of these plant populations.

- Last but not least, it is possible that the action of man in work related to fishing, such as trawling and shellfish fishing or sports activities (jet skis and irresponsible scuba diving), cause such a disaster in the depths that the populations of this phanerogam are reduced and its development is even prevented.

Author

Estefanía Espejo González

Bióloga Marina ProDunas Marbella

Do you want to receive our Newsletter?

Do you want to become a member or be our friend of the dunes?

Asociación ProDunas Marbella

The Association works tirelessly for the defence and preservation of the unique ecosystems that survive in the natural sand dune environments in the Province of Málaga; promotes the protection of native flora and small wildlife; promotes recovery, rehabilitation and conservation of interesting biodiversity of sand dunes areas in the municipality of Marbella.